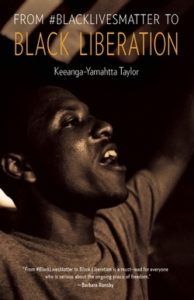

From #BLACKLIVES MATTER to Black Liberation

Review by Judy Helfand

In From #BLACKLIVES MATTER to Black Liberation Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor complicates and disturbs many of the current understandings of racism, racial history, and whiteness in the U.S., especially as these understandings are applied to organizing for freedom and justice for Black people. In the process she provides clear analysis of political and social forces working to maintain white supremacy, with insight into puzzling developments in the struggle for Black liberation, such as why #BlackLivesMatter emerged during the term of office of the first Black president.

In From #BLACKLIVES MATTER to Black Liberation Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor complicates and disturbs many of the current understandings of racism, racial history, and whiteness in the U.S., especially as these understandings are applied to organizing for freedom and justice for Black people. In the process she provides clear analysis of political and social forces working to maintain white supremacy, with insight into puzzling developments in the struggle for Black liberation, such as why #BlackLivesMatter emerged during the term of office of the first Black president.

One key concept explored in the book is the “culture of racism.” Many of the indicators of Black inequality are economic: substandard housing, unemployment, inadequate food and health care, poor schools. Social programs designed to alleviate suffering such as food stamps and welfare, don’t seem to change conditions in poor Black neighborhoods. An explanation that has appeared in many guises over the years is the notion of cultural forces that imprison folks in self-destructive modes of living, decaying their moral fiber, and leaving lazy, criminal, violent, self-defeated individuals who are incapable of lifting themselves out of poverty. “When social and economic crises are reduced to issues of culture and morality, programmatic or fiscal solutions are never enough; the solutions require personal transformation.” (pg. 48) For example, Obama supported this notion with his demand for role modeling and charity for Black youth through My Brother’s Keeper. In this way, Black problems become rooted in Black community instead of symptomatic of the problems in the U.S. as a whole. Taylor argues that racism cannot be separated from the economic problems in the Black community and also that attempting to provide “equal opportunity” is insufficient; what is required is redistribution of wealth. She also points out that a cultural explanation for Black generational poverty and having Black people as the face of poverty, deflects attention from the increasing number of poor white people, hiding the systemic causes of poverty in the country as a whole.

The chapter “From Civil Rights to Colorblindness” lays out the strategies used to undermine the victories of the civil rights era by, in part, removing the focus from race now that legally everyone had the same opportunities. Colorblindness was an important tool to accompany the ideology of meritocracy, the belief that hard work is rewarded economically. Politicians realized that the existence of a Black middle and upper class was necessary to show that economic opportunity existed, especially since demands for higher wages and entrance into higher paying jobs and professions has been a demand of the civil rights struggle. After the civil rights era the Black middle class did expand, while the vast majority of Black people remained mired in poverty. But since racial discrimination was now illegal, failure to move up the economic ladder became seen as a matter of personal failure. And this reinforces the notion of a cultural and moral cause to poverty and violence in Black communities.

In addition to more Black people joining the wealthy and middle classes, under pressure generated by the civil rights era movements more Black people were allowed into positions of power. Many hoped that Black politicians would work in the interests of the Black community but after 40 years, “Black elected officials’ inability to alter the poverty, unemployment, and housing and food insecurity that their Black constituents face casts significant doubt on the existing electoral system as a viable vehicle for Black liberation.” (pg. 103) Taylor provides many examples of Black politicians bending to the existing power structure rather than changing it. She also discusses the divide in interests between those who did obtain money and power and the greater Black community. Much of the Black elite joined with the white wealthy and upper classes in blaming poor and working class Black communities for their problems, protecting their own economic and political interests. Some of the examples provided by Taylor are quite shocking. Even established civil rights leaders took on the role of chastising Black communities for resisting material conditions through non-electoral channels.

A discussion of policing as it relates to Black communities historically, including the War on Drugs and the rise of the prison-industrial complex post-Jim Crow, leads into current times and the mass organizing around police killings. Much of this information may be familiar to those who read Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow, or watched Ava DuVernay’s 13th. Taylor also focuses on the increase in laws that essentially criminalize poverty (fines for sleeping in a car, feeding homeless on the street, etc.), the ways in which police departments finance themselves in part through fines and fees (traffic fines, fee for public defender or probation), and the vast sums of money and resources expended on police departments (including millions paid to settle civil suits). This provides a complex picture of policing, one that combines class and race, as does her discussion of Black police officers, who have failed to bring a more just policing of Black communities, as was once hoped for.

Taylor details the growth of the Black Lives Matter movement, interweaving events that catalyzed demonstrations and organizing with examples of the tensions between the old guard—politicians and elder statesmen civil rights leaders—and the emerging leadership in Ferguson and around the country. Having contrasted “the intersectional, decentralized leadership of the ‘new guard’ and the top down control of the civil rights establishment” Taylor moves on to discuss the differences within the new movement. Can effective change come from social media organizing or are actual organizations needed? How do protests become a movement? What organizational forms support strategic planning? Community building? And further, once demands are made how does one track success in meeting them? Some demands may be immediately achievable, while others require complete reorganization of society. Taylor argues that in order to sustain a movement a balance is needed so that there can be some real achievements along with an analysis that reveals necessary long-term goals.

She sees that the strength of the #BLM movement lies in its ability to reach large numbers of people by connecting police violence with other ways in which black people are oppressed. Solidarity between oppressed groups will make every movement stronger. Reflecting on Occupy, with it’s focus on “We are the 99%,” Taylor asks how such a tiny elite can dominate the vast majority whose own interest lies in transforming the existing order. The Black liberation movement needs to transform the goal of “freedom” into specific demands that lead to networks, alliances, and combined forces.

“The aspiration for Black liberation cannot be separated from what happens in the United States as a whole.” (pg 193) As indicated by her analysis of race and class throughout the book, Taylor locates the racism within American capitalism in a dynamic relationship with class exploitation. The material inequality—four hundred billionaires and 45 million people living in poverty—cannot be changed without challenging racism. She asks “if white working-class people do not benefit from capitalist exploitation, then why do they allow racism to cloud their ability to unite with nonwhite workers for the greater good of all working people?” (pg 209) In her answer she explores the creation and continuation of white identity. In effect, white supremacy is a political strategy that manipulates racial fears to maintain class rule for the elite. The prevailing ideology in the U.S. shapes its citizens with racist ideas.

Given an understanding of how people are socialized into oppressive systems, the important question is under what circumstances can those ideas change? For Taylor, effective organizing and actions must find ways to bring all oppressed groups to the table, working together with complete awareness of intersectional issues. By most measures, poor and working class Black people are worse off than white poor and working class people. Yet those white people also live lives of “poverty and frustration.” As a revolutionary socialist, Taylor wants the reader to understand that characterization of “the working class” as white and male is dangerously wrong. The working class is “female, immigrant, Black, white, Latino/a, and more. Immigrant issues, gender issues, and antiracism are working class issues.” (pg 216)

In conclusion Taylor writes that it too early to know where the current movement for Black liberation is headed. But she does know that there “will be relentless efforts to crush it because” when the Black movement goes into motion, it throws the entire mythology of the United States—freedom, democracy, and endless opportunity—into chaos.”

Black liberation implies a world where Black people can live in peace, without the constant threat of the social, economic, and political woes of a society that places almost no value on the vast majority of Black lives. . . . While it is true that when Black people get free, everyone gets free, Black people in American cannot get free alone. Black liberation is bound up with the project of human liberation and social transformation. (pg 194)

Leave a Reply