Current Struggles for English Language Learners

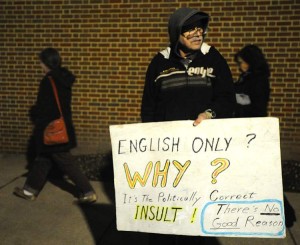

As described in Part Two of this series, “Teaching English Language Learners: History and Tensions,” by the 21st century the highly effective programs for English Language Learners (ELLs) had been largely dismantled. Students were left with a “hegemonic, English-only, homogenized curriculum… propagated in direct opposition to what is known to be effective instructional practices to help heritage language students have access to the core curriculum, develop a strong knowledge base, and understand complex content.”7.

In addition to academic setbacks, when ELL students’ primary language and culture are not supported by educators and those who shape the culture of education reform, students face a dramatic blow to their identity, their self-esteem, and their ability to successfully intermingle with their English-only peers7.

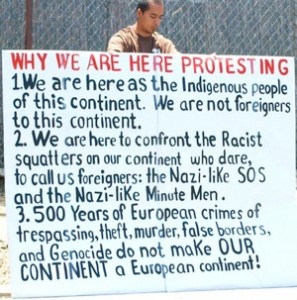

Meanwhile, persistent anti-immigration sentiments continued to run high beyond the classroom: According to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) “Anti-immigrant hate groups are the most extreme of the hundreds of nativist and vigilante groups that have proliferated since the late 1990s, when anti-immigration xenophobia began to rise to levels not seen in the United States since the 1920s.” However, unlike the physical confrontations that generally characterized hate groups of the past, these new hate mongers went a step further by  pushing racist propaganda, threatened by the illogical idea that Mexico harbored a secret “Plan de Aztlán” to “reconquer” the American Southwest.14

pushing racist propaganda, threatened by the illogical idea that Mexico harbored a secret “Plan de Aztlán” to “reconquer” the American Southwest.14

Today in California alone there are 77 identified hate groups, many of whom spread messages of anti-immigration, as demonstrated by the terrifying new messages of longtime groups like the KKK and White Nationalists, a few of whom have become involved in politics.15 But the most disturbing manifestations of anti-immigration sentiment began to take root more evidently within schools themselves, including Sonoma County.

A friend of mine—“Jordan”—attended a public school in Sonoma County following the passage of No Child Left Behind (NCLB 2002): In the tradition of Prop 187 and Prop 227, NCLB knocked English Language Learners lower on the totem pole of public image. With its passage, the Bilingual Education Act of 1968 was renamed the English Language Acquisition, Language Enhancement, and Academic Achievement Act, thereby fundamentally shifting ELL education to focus primarily on English language acquisition10 instead of supporting the students heritage language.

This was all implemented in schools where no one fully understood the requirements of No Child Left Behind, without a full cultural background informing the NCLB, and without a proper test tailored for English Language Learners. Paired with the rising tide of anti-immigrant sentiments, many immigrant students, students of color, and ELL students faced extraordinary challenges in their schools.

As a person of color, Jordan recalled encountering several factions of white supremacists in his neighborhood, but most prominently and consistently during high school. Each faction held some sort of belief against immigrants and immigration. Jordan recalls the State’s Righters, one group who dominated his high school, as very active within his school community, calling often for “separate but equal” status of immigrants and whites:

“Their stance was that America is sick and needs to be healed, and immigrants are part of the sickness. The Nazis [at my school] were explicitly racist and driven by racism, but the States Righters were driven by nationalism, but had convoluted undertones of racism.”

Jordan said their stances were cloaked in symbolism (camouflage, confederate flags, American flags, and Carhartt jackets) which were quite obvious to him and his peers who were confronted regularly. Jordan, though, was not surprised; he said that the percentage of students who participated in these anti-immigration/racist groups was equal to the percentage of racist parents, whose “presence was firmly known.” Jordan also said that “several of the teachers had confrontations with the [racist] students there” and generally defended immigrant students/ELLs.

Unfortunately, Jordan reports that the security apparatus of the school—partially external (police) and internal (teachers appointed to security positions)—reflected the racism expressed by the school’s white supremacists: “Of all my friends, I was always the one pulled aside to be searched without any reason. I was told once ‘You were in the gym,’ as reasonable cause to search me for marijuana, even though there were three whole classes of other students in the gym.”

The “attitude” of the racist students was rooted in the belief, according to Jordan, that undocumented immigrants, particularly Hispanics, were not paying taxes but using U.S. resources, bringing crime into the country, and were unwilling to work. These sentiments were often shared by then-popular icons like Rush Limbaugh:

The “attitude” of the racist students was rooted in the belief, according to Jordan, that undocumented immigrants, particularly Hispanics, were not paying taxes but using U.S. resources, bringing crime into the country, and were unwilling to work. These sentiments were often shared by then-popular icons like Rush Limbaugh:

“[L]ook at it from Vicente Fox’s point of view. I mean if — if you had a renegade, potential criminal element that was poor and unwilling to work, and you had a chance to get rid of 500,000 every year, would you do it?”17

Part Four of this series, “No Child Left Behind Damages English Language Learners Programs,” will discuss the negative impact of the Federal Education Policy, ‘No Child Left Behind’, on English Language Learners and tell how teachers work to support their students despite the racist, anti-immigrant sentiment that undermined their efforts.

————————————

For the complete series:

Part One: A Mother’s “Dilemma” and School Segregation

Part Two: Teaching English Language Learners: History and Tensions

Part Three: Current Struggles for English Language Learners

Part Four: No Child Left Behind Damages English Language Learners Programs

Part Five: White/Hispanic Segregation in Sonoma County Schools

———————-

7. Cline, et al., Zulmara. “Primary Language Support in an Era of Educational Reform.” Teacher Education 13.2 (2004): 71-85. Print.

14. “IA1b Castañeda vs. Pickard.” IA1b Castañeda vs. Pickard. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 June 2014. <http://www.stanford.edu/~hakuta/www/L

15. AP. “Court Considers Education for Alien Children.” The Telegraph [Washington] 1 Dec. 1981, N/A ed., sec. N/A: 11. <http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2209&dat=19811201&id=i6ErAAAAIBAJ&sjid=gfwFAAAAIBAJ&pg=4509,116260>

16.”Anti-Immigrant.” Southern Poverty Law Center. N.p., n.d. Web. 28 June 2014. <http://www.splcenter.org/get-informed/intelligence-files/ideology/anti-immigrant>.

17.”Inside America Hate: Ku Klux Klan”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jmc92f_4Cpg

18. Face to face interview with “Jordan”

Leave a Reply