Balm for Trying Times

by Judy Helfand

Recently various friends have asked me if I’m scared about the upcoming presidential election, which prompted some self-reflection as to why I’m not. There’s nothing surprising to me about the outpouring of hate and racial invective. Trump does not seem like the devil incarnate, simply another manifestation of U.S. politician. Then I realized I’ve been focusing on U.S. history in my reading lately (e.g. Roxanne Dunbar’s Indigenous History of the United States) and just finished The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition by Manisha Sinha, a history of the abolition movement. Maybe this reading was helping me maintain an even keel.

Recently various friends have asked me if I’m scared about the upcoming presidential election, which prompted some self-reflection as to why I’m not. There’s nothing surprising to me about the outpouring of hate and racial invective. Trump does not seem like the devil incarnate, simply another manifestation of U.S. politician. Then I realized I’ve been focusing on U.S. history in my reading lately (e.g. Roxanne Dunbar’s Indigenous History of the United States) and just finished The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition by Manisha Sinha, a history of the abolition movement. Maybe this reading was helping me maintain an even keel.

A mere 200 years ago the country was divided as antagonistically as it is today, with slavery as the flash point. Presidents and the Federal government were just as effective at preventing any real dialog, at avoiding action on important issues, and at punishing radicals agitating for change while effectively rewarding the monied classes as they are today.

The Slave’s Cause is the first book I’ve ever read focusing entirely on the abolition movement. I knew very little about the movement or the people who made it. Nor did I know much about the continuing contesting of slavery from before the revolution through the Civil War in personal, public, electoral, judicial, economic, and educational spaces. Somehow my education gave me the impression that “people back then” held different ideas about slavery and although we had to fight a war to end slavery in the U.S., it was a gradual tide of changing opinion that brought about the end of the “peculiar institution.”

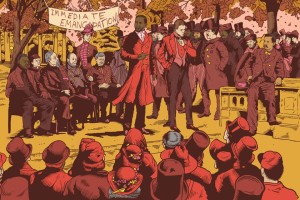

Support for slavery came from the north and the south, with the comfortable elite in the north willing to live in “free” states but unwilling to endorse abolition of slavery throughout the country: their economic well-being was firmly linked with slavery. Governments and mobs worked together to prevent the spread of abolitionist ideas by preventing tracts from being sent via Federal mail, burning down printing shops that printed abolitionist newspapers, passing gag orders to prevent Congress from accepting petitions against slavery, closing down schools started by abolitionists, attacking abolitionist speakers and often their audiences as well while the police stood by. As I read about this I kept imagining how each of these individual events inspired fear, despair, and re-commitment to the fight for the individuals in the abolition movement, much as we respond to events today.

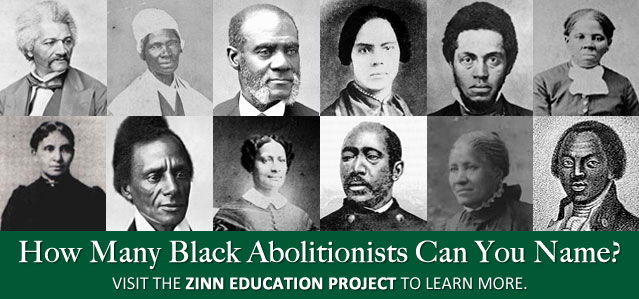

Black men and women, both those who were free and those who had escaped from  lifetime chattel bondage, constituted a large portion of the abolition movement. And white women at times outnumbered white men, although not in positions of leadership as many of the abolition societies did not allow women to hold elected office. Some societies were all-black, and had theoretical foundations to support separatism. Others were mixed, and some were all white. There were religious and secular organizations. Some abolitionists were radical: end slavery now, no compensation to slave holders, make black men and women citizens, extend the vote to women, and more. Others called for a more gradual approach and didn’t necessarily want to take on human rights issues beyond ending slavery. Reading of all the disagreements, restructuring of organizations, petitions and demonstrations to push or thwart radical ideas brought abolitionism alive for me. I could compare it to my own engagement with radical causes and the disappointments and successes along the way.

lifetime chattel bondage, constituted a large portion of the abolition movement. And white women at times outnumbered white men, although not in positions of leadership as many of the abolition societies did not allow women to hold elected office. Some societies were all-black, and had theoretical foundations to support separatism. Others were mixed, and some were all white. There were religious and secular organizations. Some abolitionists were radical: end slavery now, no compensation to slave holders, make black men and women citizens, extend the vote to women, and more. Others called for a more gradual approach and didn’t necessarily want to take on human rights issues beyond ending slavery. Reading of all the disagreements, restructuring of organizations, petitions and demonstrations to push or thwart radical ideas brought abolitionism alive for me. I could compare it to my own engagement with radical causes and the disappointments and successes along the way.

The radical abolitionists, black and white, put forth an uncompromising message on the hypocrisy and corruption of the United States as a nation. They wanted to reform society and transform the state. Some black abolitionists called out to abolish the myth of race much as we describe race as a social construct today, “trying to chart a course between rejection of all forms of racism and identity based on racial oppression.” Black abolitionists also countered the racial pseudo-sciences that evolved during the early 19th century, propagated by elite such as Louis Agassiz who was president of Harvard. In one of my favorite quotes, Maria Chapman observed that “in a few words black abolitionists could convey an argument against racial prejudice that might take a white man all day.” (pg. 328)

All of this organizing took place alongside death, torture, and destruction. Although non-violence was a core value for many radical abolitionists, self defense was often approved. Black men organized defense groups, with some white men participating as well. The myth that slaves did not resist was disproved through escape, revolt, work stoppages, sabotage, and underground organizing. Many of the tactics we use today were used then, including “buy free goods” campaigns, which were a boycott of goods produced through slave labor.

This 700-page book is one I am happy to have on my bookshelf. I did not read closely every section: it is packed with details. But all traces of my mainstream education on the abolition movement are disrupted if not erased. And the posturing and hate-mongering rampant this election season are put within a historical context where they properly emerge as an American tradition. While abolitionists did celebrate the ending of slavery, the victory was partial and black equality never achieved. “Abolitionists wrote their memoirs even as disenfranchisement, segregation, debt peonage, and lynching made a mockery of black freedom.” (pg 590). The struggle for racial justice continued, along with the struggle for women’s rights, workers’ rights, and many other struggles for freedom and justice for all in United States. The abolitionist call to action stirs many of us today.

Leave a Reply