A Deeper Multiculturalism: A Review of the Children’s Book Jack & Agyu

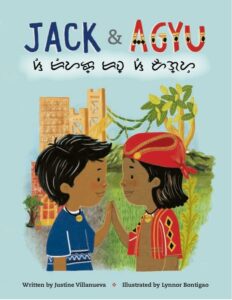

A Deeper Multiculturalism: A Review of the Children’s Book Jack & Agyu, written by Justine Villanueva and Illustrated by Lynnor Bontigao.

Winner of the Gold Medal for the Benjamin Franklin Award for Children’s Picture Book from the Independent Book Publishers Association

By Christopher Bowers

Jack & Agyu is a children’s book written by Justine Villanueva and illustrated by Lynnor Bontigao that is both subversive and celebratory. Published by Sawaga River Press, a publishing company devoted to books about children’s experiences in the Filipino diaspora, this children’s book simultaneously offers a cultural critique and an inspiring vision.

The book begins with a child named Jack noticing he is not represented in his own children’s books, that all the characters in the children’s books he’s checked out from the library are white. Initially, not seeing people that look like him in his books makes him feel that maybe he does not deserve the same kind of adventures or opportunities as the characters in his books. But his disappointment soon is overtaken by inspiration. Using a crayon, young Jack colors the white-washed characters of his books brown, “brown like the champorado, the chocolate rice porridge that his lolo, his grandpa, often made him for breakfast. Jack & Agyu is full of wonderful and sensual cultural touchstones like this.

When Jack’s mother discovers what he has done to the library books she offers to him a story of his own culture, with a main character that happens to look a lot like him. This is the story of Agyu, a powerful character in Ulaging (a tribe of indigenous people in the Philippines) who fights for the freedom of his people.

What makes Jack & Agyu particularly powerful is its ability to go beyond feel-good, white-liberal notions of multiculturalism by honoring its cultural subject more deeply. In Jack & Agyu we do not find a simply singular historical hero or stereotypical cultural traits to celebrate, or pleas to recognize similarity across difference (read pleas to forget difference). Instead, we find a cultural story full of depth and complication, yet simple enough to captivate and inspire a child. We find colors connected to memory and remembering tied to survival. While the story of Agyu is an indigenous story, we are not asked to remember some monolithic “native” culture in some idealized or stereotypical fashion. Rather, we are inspired to consider what these old stories might mean for a new generation.

For example, What can Agyu’s offerings to a traditional healer teach children about gratitude, humility or elders? What can Agyu’s attempt to get permission to hunt from diwata, the guardian of the forest, teach children about ecological courtesy, about climate change, or about food systems (then and now)? In this way, Agyu’s cultural context is also medicine for people from all cultures, and their children.

As well, the book has in-depth descriptions of culturally significant words, objects, and people for it’s adult and advanced readers. More than that, the book offers it’s own translation of the story in three different Filipino languages. This functions to truly honor the various cultures within the Philippines, which of course is not itself a monolithic culture. And in the U.S., where too often it is insisted upon that English as the one and only language of the country, this offers children a perspective of how different cultures can co-exist without erasing the beauty of one another. This book is thus suited for children of almost any age. The story of Jack and Agyu reveals how the process of “othering” begins at a tender age and how the power of cultural storytelling is a potent antidote to such dehumanization. This is an important lesson for children of all ethnicities growing up in troubled and oppressive times.

Leave a Reply