Ancestral Land Claims

by Judy Helfand

My friend offered to do some genealogy research for me. I already had a fairly extensive genealogy and history of my father’s side, the Jewish side. My paternal grandmother and grandfather emigrated to Canada and the US in the late 1800s and early 1900s. I suspected some of my maternal ancestors had arrived very early in what became Pennsylvania and New York, although I knew little of the history, so I asked my friend to focus on my mother’s side of my family. When she delivered the results of her research and I started reading I was shocked to discover documentation of my ancestors obtaining land. I didn’t expect to find such an immediate connection to taking land from the Indians at the time of colonization. Even knowing that, on my mother’s side, there were ancestors here very early, it simply never crossed my mind. I’d always imagined them coming as indentured servants.

When I started to read through the findings there were two explicit mentions of ancestors obtaining “warrants” to land in Pennsylvania, and in both cases there was mention of the Indians who had been living on that land.

In 1709 several Swiss Mennonite families “selected 10,000 acres on the north side of Pequea creek, in West Lampeter and adjoining townships; and in 1710 they obtained a warrant for this land, which they divided among them in April 1711. . . . The settlement now consisted of thirty families. With the Indian tribes of the vicinity—the Conestogas, Pequeas and Shawanese—they lived on the most friendly terms, mingling with them in hunting and fishing. Their annals speak of the Indians as being “hospitable, respectful and exceedingly civil.

from Brief History of Lancaster County published in 1892

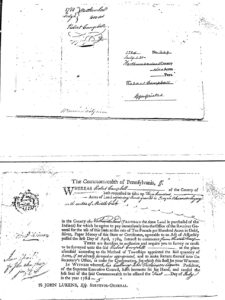

Whereas Robert Campbell of the County of Northumberland hath requested to take up four hundred Acres of Land adjoining land granted in [illegible] and the water of Middle Creek in the county of Northumberland (Provided the same Land is purchased of the Indians) for which he agrees to pay immediately into the Office of the Receiver General for the use of this State at the rate of Ten Pounds per Hundred Acres in Gold, Silver, Paper Money of this State or Certificates, agreeable to an Act of Assembly passed the first Day of April, 1784, Interest to commence from the date hereof.

These are therefore to authorize and require you to survey or cause to be surveyed unto said Robert Campbell at the place aforesaid, according to the Method of Townships appointed the said quantity of Acres, if not already surveyed or appropriated, and to make Return thereof into the Secretary’s Office, in order for Confirmation, for which this shall be your Warrant.

Reading of the land purchases in 1709 and 1784 by my ancestors drew me in closer to the immediacy of colonization and genocide and displacement of the indigenous people living in what became the US. I’ve been thinking about it for days now, trying to identify my feelings. First, I had to question why I had always pictured my first ancestors to arrive on Turtle Island as indentured servants. Early colonial history taught in schools seems to provide two categories of colonists: those fleeing religious persecution and those fleeing poverty by indenturing themselves to obtain passage. The relatives I knew on my mother’s side of the family were working class and I never heard stories to indicate it had ever been otherwise. Also, I never thought deeply about it, accepting my fantasy of indentured servants. So, although I certainly acknowledged myself as a settler and recognized and was purposefully educating myself about the impact of European colonization on the original caretakers of the land, it remained semi-academic, more a story than a living, breathing series of events involving complex human beings.

Second, after seeing the evidence of land purchases, I immediately wanted to know the history of what was happening at that time, especially to the Indians in those places. Most of what I’ve found was recorded by the colonizers. In those histories were the details of gradual settlement by Europeans and the displacing of Native Americans, with those displaced trying to find a new place to settle without disrupting other Native American nations. There is mention of inter-Native American wars and enmities, some apparently older than the arrival of the Pennsylvania colonists and some directly attributed to colonists taking land and forcing Indian villages to move. Also, the fur trading and French settlements had been a disruptive element for native people since the 1500s. Hours passed as I read accounts, following up on new clues. I searched through the official webpage sites of the Indian nations mentioned as living in the area where my ancestors settled to see if they contained tribal histories. Ultimately, I came away knowing that there were complex political, social and cultural relationships among the many indigenous peoples who inhabited what became the northeastern U.S. and eastern Canada. The contact with Europeans had devastating impact on those people and learning about it would require more than a few intensive forays into internet materials.

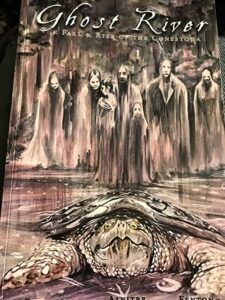

In these internet searches I found few mentions of European colonists killing Indians in any organized fashion, although I know this must have been happening. One exception I found detailed the massacre of the Conestoga Indians of Lancaster county in 1763. This event was also documented by a graphic novel created and published by Native Americans, Ghost River: The Rise and Fall of the Conestoga from Red Planet Books. This was the area where my Mennonite ancestor settled.

In these internet searches I found few mentions of European colonists killing Indians in any organized fashion, although I know this must have been happening. One exception I found detailed the massacre of the Conestoga Indians of Lancaster county in 1763. This event was also documented by a graphic novel created and published by Native Americans, Ghost River: The Rise and Fall of the Conestoga from Red Planet Books. This was the area where my Mennonite ancestor settled.

Mixed in with the histories of what was taking place in Pennsylvania were some detailed accounts of why my land-buying Mennonite ancestor from 1709 came to Pennsylvania. The following is from a private website compiled by Cynthia Swope detailing the history of the several Mennonite families who came to Lancaster county.

Our Mennonites were part of an Anabaptist tradition with roots in Switzerland & Germany, predating the Amish who splintered off from them. Involved in Anabaptist doctrine was a refusal of carnal warfare, a shunning of worldly possessions, and central was the refusal of baptism until the age of cognizance, usually around 12 years of age, when other protestants [and Catholics] experience first communion. The concept of refusal of infant baptism was heretical to both non Anabaptist protestants and Catholics alike, occurring in an era when infants who died before baptism were commonly buried separately from their parents. Mennonite children were seen as swine dirtying the streets, Mennonite men as impossible subjects who preferred jail to the wars ravaging Germany for which they were felt needed and in which their conscience would not allow involvement, the group as a whole seem often to be considered an unwelcome pestilence. First practicing in Switzerland and the Palatinate of Germany in the 1520s, as a group Mennonite Anabaptists had suffered vigorous persecution which, in the worst scenarios, involved torture, death by drowning, beheading and burning at the stake, confiscation of properties, expulsion from villages sometimes in the dead of winter and without shoes on their feet, and, in the best of scenarios, the outlaw of their religious practice and the threat of imprisonment in rebellion of the law, absence of legal recognition of marriage, the ban on funerals in the faith, and social stigmatization. from Within the Vines website

Now I can picture my Mennonite ancestor, Hans Herr, living in his community, first near Zurich, and then moving to the Palatinate in northern Bavaria, as the community fled persecution. This persecution did not consist simply of laws prohibiting worship in his faith, as I always imagined , but a horrific litany of measures designed to erase the Mennonites. This real man, 75 years old, in the company of others who had experienced the same wars and persecution in Europe, fled to the “promised land” where William Penn had offered them sanctuary and the promise of land for farming.

Arriving in Pennsylvania, looking for land, and then purchasing 10,000 acres to be shared among several families, what did he know or think of the presence of Conestogas, Pequeas and Shawanese? Did he know of the displacements and disruptions to their way of life begun in the 1500s with French fur trading and continuing to that day? Did he ever discuss his religious and world views with an Indigenous elder and learn about Conestoga or Shawnee world views and religion? I find it difficult to even imagine how European Protestants could have ever coexisted peacefully with people who did not see humans as “having dominion” over creation and who claimed territory while never claiming ownership and the right to use it to their own purposes. Europeans by the 17th century were hundreds of years removed from tribal, animist or pagan roots, those roots having been relentlessly severed by the Catholic church over centuries of edicts, punishments, enforced worship and education, and ultimately, killings.

So my ancestor probably went about his life focused on the needs of his community, in establishing farms and homes and church, possibly trading with Indians or learning from them about the geographical features of the area and the medicinal properties of some plants, without any real recognition or acknowledgement of the negative impact of his arrival. Given his religious beliefs it seems unlikely that his community was involved in any wars against the local indigenous people, yet he may have known of campaigns to “clear” the land of “troublesome” Indian bands and not protested. The brick building pictured was built in 1719 as the first Mennonite meeting house and was built on the Hans Herr homestead.

So my ancestor probably went about his life focused on the needs of his community, in establishing farms and homes and church, possibly trading with Indians or learning from them about the geographical features of the area and the medicinal properties of some plants, without any real recognition or acknowledgement of the negative impact of his arrival. Given his religious beliefs it seems unlikely that his community was involved in any wars against the local indigenous people, yet he may have known of campaigns to “clear” the land of “troublesome” Indian bands and not protested. The brick building pictured was built in 1719 as the first Mennonite meeting house and was built on the Hans Herr homestead.

My other ancestor for whom I have a record of land purchase was Scots-Irish, a descendant of those Scottish sent to Ireland by the British to colonize Ireland and subdue and control the Irish. (The British developed a system that was later utilized in colonizing Virginia, South Carolina and surrounding areas, with Scotts-Irish as the enforcers of the plantation system and the accompanying enslavement of African people that enabled it.) After some research into these ancestors I came away confused by dates and possible mistakes in attribution as the Robert Campbell who seems to be in my family line would have been 12 years old when the land was purchased. Other references to a different Robert Campbell appear in the histories I could find. Regardless, these Campbells became farmers and did obtain land at some point. The warrant states that the land requested can be purchased from the Commonwealth “provided the same land is purchased from the Indians.” I found that in 1784 Indian representatives signed a treaty in which the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) ceded the northwestern corner of Pennsylvania (most of the rest of Pennsylvania had already been ceded earlier). However, the 6 Nations Council of the Iroquois Confederacy refused to ratify the treaty. Nonetheless, Pennsylvania offered the land to settlers in 1784 and Robert Campbell was among those who succeeded in obtaining a warrant. What is interesting is that early on people did think about the land in relation to its traditional caretakers, at least making a pretense of having acquired it legally. Title to land I hold in Sonoma county makes no reference to the Wappo and Pomo people who lived here and never ceded the land at all.

The earliest I have known ancestors in the U.S. is 1709. That ancestor, Hans Herr, born 1660, is one of 512 ancestors on my mother’s side in that generation. To learn the history of what sent all my ancestors across the seas and how their arrival affected the lives of Native Americans already here is a daunting task, not one I will necessarily undertake. Nor will I likely immerse myself in the history of Native Americans in Pennsylvania and surrounding areas before and during colonial times. I will pay attention to any stories/histories that cross my path touching on any of these areas and make an effort to continue to fit the pieces together to produce a more informed picture of colonization. I especially hope to uncover stories of European settlers who made efforts to understand the native people they encountered and actively worked to find ways to live in harmony with them, much as I have looked for the stories of Abolitionists and others who resisted the enslavement of and trade in African people and their exploitation in this country. For now, I need time to let this all percolate.

Leave a Reply