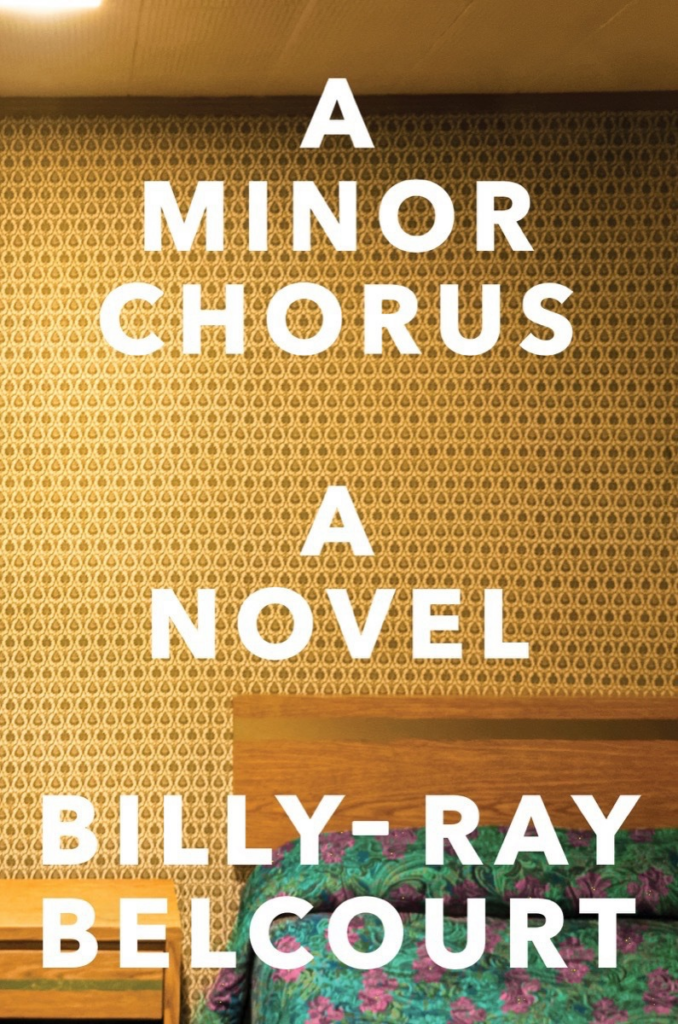

A Post-Modern Queer Interrogates Cree Homosexual Life

Review by Adrienne Lauby

This is a simple little book on the face of it, 159 pages which describe the return to a hometown and home reservation in a format similar to a diary. But, this narrator sets out to capture the truth of a contemporary indigenous (Cree) queer life, and that turns out to be anything by simple.

Billy-Ray Belcourt dedicated this novel to his “Kokum, who made all my writing possible.” And again, it’s simple. Dedications to parents, or in this case a grandmother, are very common. But in this book the Kokum is both someone worthy of personal appreciation and one of the few hedges against the long-term ravages of colonialism. Not simple.

Belcourt’s narrator is a doctoral student writing a dissertation on the grief of being queer and Cree in a settler state. He takes time off to travel to his childhood home in Northern Alberta and write a novel. Once there, he talks to people, reflects on the conversations and writes this book.

From planned interviews to time with family members to casual hookups for sex, everything is fodder for the narrator’s post-modern introspection. What does it mean to be a gay man, a homosexual, in a rural area? How is surveillance the same inside and outside a prison? What does one do about the indeterminacy of feelings? Does place govern the practice of self-fabrication? Is there a romance of the negative?

If the sentences and phrases of the previous paragraph confuse you, if you are you saying to yourself, “What the heck does he mean: ‘romance of the negative,’” you are not alone. Unless you have been immersed in post-modern academic theory, the language of this book will be difficult.

Billy-Ray Belcourt’s narrator says as much.

“I was interested in how a singular voice, when heard from a sociological distance, implicated a larger population, in how the autobiographical was rarely an individualistic mode; all of its wonder and devastation was social. I knew I couldn’t articulate that interest in those terms. It would sound like nonsense to Michael, as so much of my academic writing and thinking would. I often questioned what use that language was when it alienated so many.”

He’s right. This language can sound like nonsense, and it can quickly alienate. And yet…. as I continued reading about the struggle of the narrator to understand his life, his personal relationships and his tribal history, these abstractions began to seem like clues.

The more chapters you read, the easier the language becomes. The last 8 ½ pages are almost entirely in the voice of Jack, a childhood friend who is awaiting trial in prison. Jack tells what seems to be a simple story: “My fate was determined from the start. The drugs, the dealing, the alcohol, they let me be more than what I was. They freed me from myself.”

But, because of all the questions that were raised and remain unanswered by the earlier pages of this book, I couldn’t read even this straight-forward telling as simple.

In the end, I don’t appreciate this book for the facts, insights or even emotions it gave me about the life of a Cree queer. I treasure it because I gained less certainty, less expectation for stories with a tidy conclusion and a hint of the questions these characters might be asking themselves.

Art is often about telling the reader, viewer, listener something they didn’t know. Not factually, although there are times it is factual. The great stuff picks you up, spins you around and puts you down in a different place, a place you didn’t know existed although you may have lived there your entire life.

A Minor Chorus by Billy-Ray Belcourt is this kind of art.

Leave a Reply